Tu B’Shvat – Why Israel?

In Israel, even the fruit we eat and the land upon which we walk, has the potential to transform us. It’s possible to lead a Torah life outside of Israel, but the very essence of this place pushes us to new heights. No land anywhere else in the world can do that!

“Here, talk to my grandma,” my friend said as he shoved the phone to my ear. I had just returned home from the Beit Midrash, and was ready to engage in the coveted activity that marked the conclusion of my day — the late night work-out. There I was, dressed in my ripped undershirt, wearing my old weight-lifting gloves, when I was asked a very difficult question. Unlike the usual, “Why are you wasting your time studying ancient texts?” my friend’s grandmother asked me, “Why do you study in Israel?” She had a point. After all, accommodations in America are superior, our families are closer, and our holy texts have remained the same for thousands of years and in every place where the Jewish people have settled. I was stumped. At the time, I did not realize that the answer to her question lay in a holiday I didn’t understand.

Rosh Hashanah of the Trees

Tu B’Shvat is called the Rosh Hashanah of the trees. But this doesn’t mean to hug a tree like we do in California, or even to eat honey and apples for a sweet New Year. No balls drop in Times Square, Dick Clark isn’t the Master of Ceremonies, and few people make resolutions. People leave those stupid party hats at home, and no one consumes round challah. Really, the only tradition practiced on this day is to eat fruit grown in Eretz Yisrael. This practice highlights the fact that Tu B’Shvat is a halachic marker, rather than a “New Year” in the traditional sense.

Farming is important in Eretz Yisrael. In addition to being a source of national income, it gives the people living in Eretz Yisrael the opportunity to do many important mitzvot. There are special laws for produce grown in Israel which entail separating, or tithing, part of the crop. Tu B’Shvat, the 15th of Shvat, is the date by which the food that has been grown until this time is required to be tithed separately from the produce grown afterwards.

But what relevance does this have to those of us who are not farmers? Perhaps more than we might think. In many places, the Torah compares people to trees. The Torah teaches us, “When you besiege a city for many days to wage war against it…do not destroy its trees — is the tree of the field a man [and therefore worthy of being destroyed]?” (Devarim 20:19).

Man and Tree

The Maharal of Prague explains that there is a profound connection between a man and an eitz, one of the two Hebrew words for a tree. An elon is a tree that bears fruit, whereas an eitz can be either a fruit-bearing or non-fruit bearing tree. Eitz refers more to the physical structure of the tree, and elon refers to the character of the tree. The word eitz is composed of the letters ayin and tzadee.

The letter tzadee is very similar to tzaddik, a righteous individual. In Hebrew, the word ayin means “to look.” Thus, eitz in Hebrew can be read as “ayin tzaddik,” or “look to see a tzaddik.” The Maharal points out that by looking at a tree one can understand the physical make up of a righteous person. A person’s body resembles a trunk, his limbs are like branches, and his hair can be compared the multitude of roots that extend out from the trunk. Yet upon examining a man and a tree, it is evident that one of the two is upside down! A tree’s roots are in the ground, whereas man’s “roots,” his hair, is facing the sky.

The Marahal explains that a tree is rooted in the ground because that’s where it draws the nutrients it needs to survive. Even if one were to cut off a tree’s branches, the tree can survive as long as its roots remain in the earth. Similarly, a person whose “roots” or essence is connected to spirituality is considered a righteous individual, an “Eitz.”

Tu B’Shvat is called the Rosh Hashanah for elonot, fruit-bearing trees. Tzaddikim and scholars are likened to fruit trees. Their “fruits” are their good deeds and Torah knowledge which can be harvested and enjoyed by the nation of Israel. Rabbi Zev Leff offers a profound understanding of the connection between fruit-bearing trees and holy people.

Rabbi Leff explains that elon is spelled alef, yud, lamed, nun. If we separate the alef from the rest of the word, we are left with the letters yud, lamed, and nun. The numerical value of these three letters added together is ninety, which is the same numerical value as the word tzaddik. In Hebrew, the word elef, or alef, means ‘to teach.’ Thus, the elon means “learn-tzaddik.” We can learn to be righteous by studying the laws that apply to elonot, the fruit-bearing trees grown in Eretz Yisrael.

The four primary tithing that are to be taken from Israeli produce are known in Hebrew as trumah, ma’aser rishon, ma’aser sheini, and ma’aser ani. In addition, we take the bikurim, the first fruits that a farmer harvests, and separate them from the rest of the crop. We then designate this portion to God. This represents a beautiful concept that has great relevance for the Jewish people. Farming is hard work. A farmer must prepare the field, invest in the seeds, and care for the young plants. His labors bear fruit (pun definitely intended) when he is able to harvest his first crop. A successful crop is likely to lead the farmer to pat himself on the back for what he perceives as his great accomplishment.

Tithes to Hashem

Yet the farmer really doesn’t have that much to do with the success of his crop. After all, without fertile soil, proper rain, and the proper climate, there would be no crop. Thus, despite the farmer’s hard work, God’s gifts were really the key to his success. Through separating the bikurim, we remind ourselves that it is God’s blessing, rather than our efforts (although our effort is necessary of course) that bring about the success. In addition, the first of anything always establishes a precedent. The first is the root. Thus, we dedicate our first fruits to God, so that the entire subsequent crop can similarly be rooted in holiness.

The second tithe includes trumah and ma’aser rishon. In order to take trumah, a person separates 2% of the produce and dedicates it to the Kohanim (priestly class). They then separate ma’aser rishon, which is another 10% to be given to the Levites. The ma’aser rishon supports the Levites, to enable them to perform their duty in the Temple without having to worry about making a living. Since the Temple is no longer standing, we do not give trumah or ma’aser to the Kohanim or Levites. Instead, we separate and destroy this designated produce.

The number ten, the percentage separated for the Levites, symbolizes unity. We are instructed to pray in a minyan, which is a gathering of ten men. A minyan fuses many different people together in a single, holy body. The number ten represents the fusion of a diverse group into a common cause. The common goal represented by ma’aser rishon is to support those who serve us in the Temple, which is a requirement for the entire nation of Israel. Thus, by taking trumah and ma’aser rishon, we acknowledge that all that we have is united in the service of God, which in turn links us to our duties as a holy nation.

Today, in the era following the destruction of the Temple, we do not actually give a tenth of our fruit to Kohanim. However, we still separate our fruit and thereby declare that a tenth of it (nonetheless) belongs to the Kohanim.

By taking trumah and ma’aser rishon, we have established that our primary goal in harvesting fruit is to foster a connection with God. We also recognize that we are part of a unified nation, with a single national goal. Thus far, our tithes represent our desire to incorporate spirituality into our lives. Yet we must learn how to practically accomplish this!

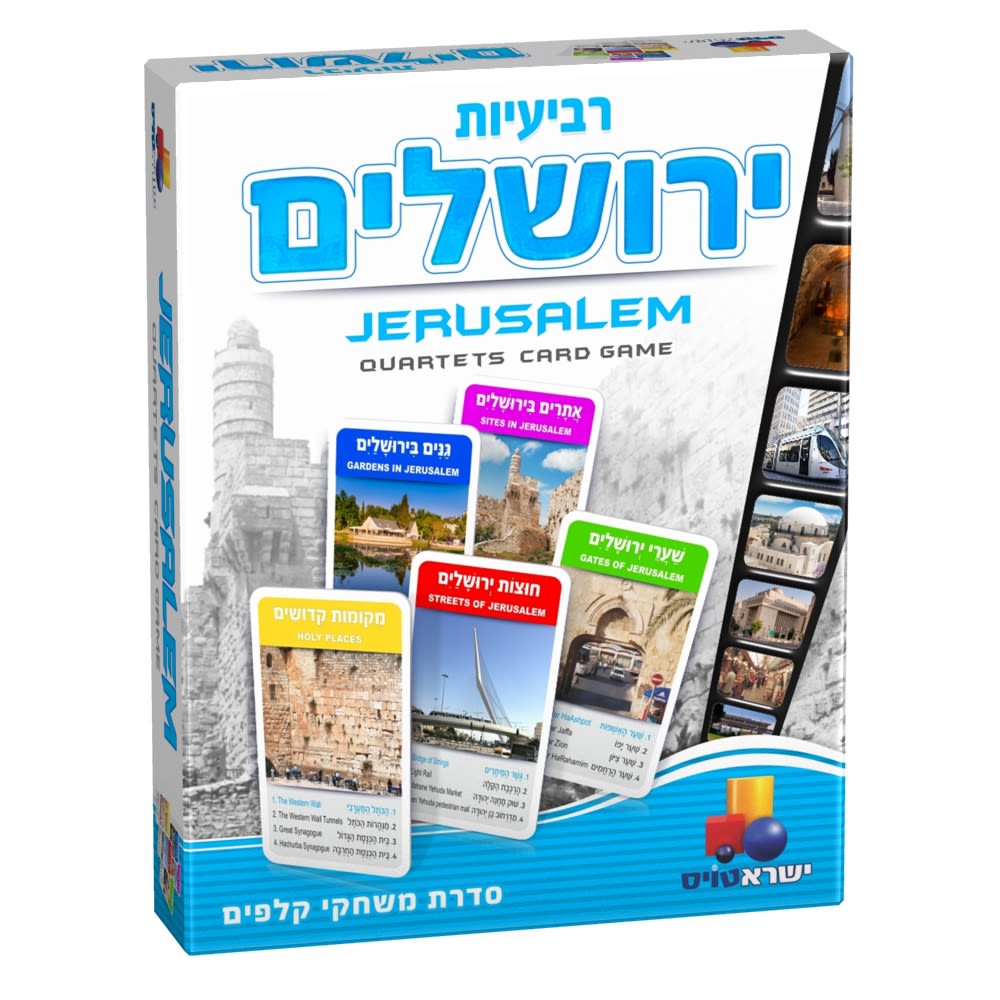

Jerusalem

During certain years of the seven year cycle (year 1, 2, 4, and 5) another tenth of our harvest was taken for ma’aser sheni. We were obligated to take this part of our produce to the Holy City of Jerusalem, and eat it there. Should we have too much fruit to carry, we could redeem our produce for money, and then go spend the money in the Holy City.

In the days when the Temple stood, the city of Jerusalem was truly a magnificent place. The Sanhedrin, the Holy Court, convened there. The city was the focal point of Torah learning in the world and was home to the most prestigious rabbis and greatest yeshivot. A person could visit the glorious Beit Hamikdash, and experience the Kohanim making the sacrifices, and the Levites singing their praises to God. A person who brought a tithe to Jerusalem could bask in the glory of Judaism in a way we cannot even comprehend today. A person could truly experience spirituality and learn about the mitzvot from the masters of our faith. Here they could connect with and be a part of the Torah that came forth from Jerusalem.

The Poor

Lastly, the final tithe was taken during the third and sixth year of the seven year cycle (when ma’aser sheini was not separated) was called ma’aser ani, the portion we set aside for the poor. God is the ultimate source of our wealth. The reality that poor people exist and have always existed represents the fact that the less fortunate have a crucial role to play. After all, if God wanted to eradicate poverty, He certainly has the means to make every person a millionaire. Rather, as the Ramchal says, the point of life is to imitate God in order to have a greater appreciation of Him. He apportions His goodness unequally to enable the more fortunate to give to the less fortunate, and thus both the person who gives and the person who receives can learn to appreciate and relate to the Almighty. For this reason, we are halachically obligated to give part of our crop to the poor.

The four tithes teach us that: (1) our core is rooted in the spiritual, and all of our accomplishments ultimately stem from the gifts given to us by God; (2) despite our individuality and the diversity of talents we possess, everything must be unified in the service of God; (3) to translate our lofty spiritual goals into practical reality, it is necessary for us to learn how to live a proper, upstanding Jewish life. This is accomplished through our association with those who live immersed in Torah; (4) the end product of our spiritual growth is to mirror the actions of God, which is done through caring for the needs of others who are less fortunate than us. Anyone who lives life in this fashion is a righteous individual, a tzaddik.

Rabbi Leff explains that each tithe can be represented by a letter. Trumah is represented by the letter alef, the first letter in the Hebrew alphabet. Ma’aser Rishon, taking a tenth of the produce for the Kohanim, is represented by the letter yud, the 10th letter of the alphabet. Ma’aser sheni, which represents going to Jerusalem to learn how to translate our spiritual potential into reality, is represented by the letter lamed for the Hebrew word lomed, to learn. Finally, the Hebrew word nofal means to fall or be lowered, representative of the poor person for whom we set aside ma’aser ani. This tithe is represented by the letter nun, the first letter of the word nofal. When you put together the four letters that represent the tithes, you get alef, yud, lamed, nun, which spells elon, the fruit-bearing tree. Thus from elon, we can learn how to become a tzaddik.

Says Rebbe Nachman, “Through the holiness of the land of Israel, one can attain pure faith” (Likutey Etzot, p. 29). The underlying message of Tu B’Shvat is the profound holiness of Eretz Yisrael. Other places in the world might stir a person’s emotions with its jagged mountains, serene coastlines, or rolling hills. There are countries in the world with holy people and places awash with history. Yet there is no place like Eretz Yisrael. In Israel, even things as seemingly mundane as how to harvest fruit have the potential to uplift a person and turn him into a reflection of the Divine image.

This is the answer to my friend’s grandmother’s question. In Israel, even the fruit we eat and the land upon which we walk, has the potential to transform us. Sure it’s possible to lead a Torah life outside of Israel, but the very essence of this place pushes us to new heights. Perhaps the reason why people who live outside of Israel eat Israeli produce on Tu B’Shvat is to remind them that that which this land produces cannot be reproduced anywhere else in the world. Other places might have bigger fruit, less expensive fruit, or more choices of fruit, but no other country can produce holy fruit. Therefore, in spite of the fact that we live scattered across the globe, for thousands of years we have longed for, and looked towards, our beautiful, holy homeland because there is truly no other place like it on the face of the Earth.

Tell us what you think!

Thank you for your comment!

It will be published after approval by the Editor.