Ekev: Bound to His Father

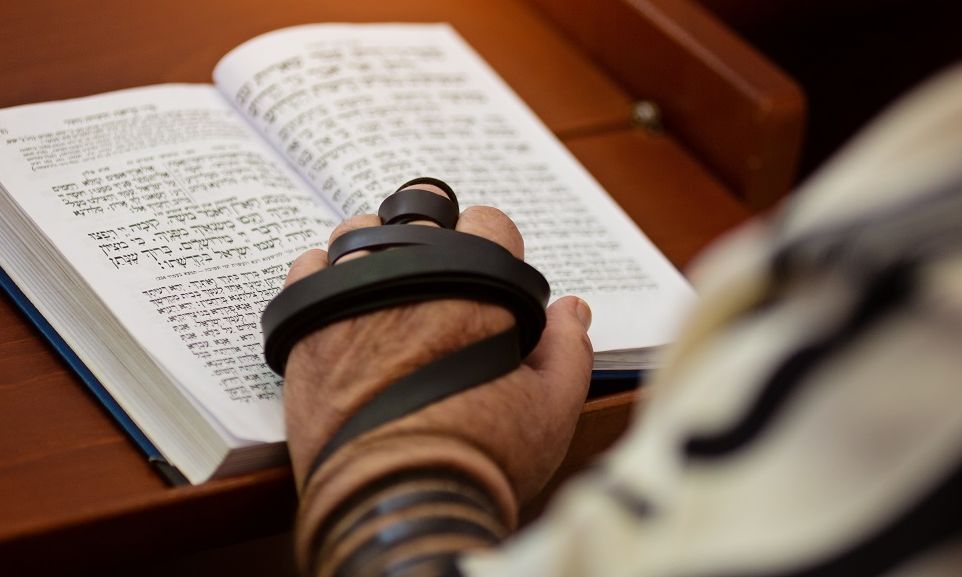

The man didn't answer. Instead he was staring down at the straps of tefillin wrapped on his left arm, caressing them with his right hand and repeating...

In this week’s parsha, Parshat Ekev, we learn about the mitzvah of Tefillin. “Bind [these words] as a sign on your hand, and let them be an emblem in the center of your head” (Devarim 6:8).

The following story was reprinted from Reflections of the Maggid – Inspirational Stories from around the Globe and around the corner, by Rabbi Paysach Krohn with permission from the publisher, ArtScroll/Mesorah Publications Ltd. http://www.artscroll.com and with permission from the author, Rabbi Paysach Krohn www.brisquest.com

* * *

In the summer of 2000, 16-year-old Mordechai Kaler volunteered to help in the Hebrew Home of Greater Washington in Rockville, Md. One of his responsibilities was to invite the residents to attend the daily services (minyan) in the synagogue on the first floor. Some agreed and others refused, but even those who declined were pleasant about it.

There was one man on the second floor, however, who had been quite nasty and had even cursed another volunteer when he was asked to join the minyan. The volunteer was taken aback by the man’s tirade, so Mordechai undertook the challenge of speaking to the angry gentleman.

Mordechai found the man sitting in a wheelchair in a lounge filled with residents of the home. After introducing himself, Mordechai said softly but firmly, “If you don’t wish to join the services we can respect that, but why should you curse the volunteer? He is here to help and he was just doing his job.”

“Young man,” the elderly gentleman said sternly, “wheel me to my room. I want to tell you a story.”

When they were in the room alone, the old man told his story of horror, pain, and sadness. He came from a prominent religious family in Poland and when he was 12 years old, he and his family were taken to a Nazi concentration camp. They were all killed except for him and his father.

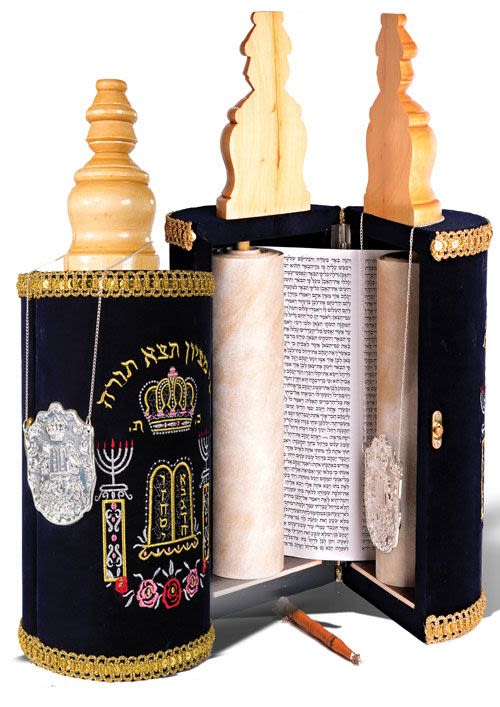

In their barracks there was a man who had smuggled in the tefillin shel rosh, the leather black box containing biblical passages worn on the head during morning prayers. Every day the men in the barracks would try to seize an opportunity to put on the religious gear, even for a moment, when there were no Nazi S.S. guards nearby. The men knew that they hadn’t fulfilled the religious duty because they were missing the second part of the tefillin, for the hand, but their love for doing the Creator’s commands compelled them to do whatever they could.

The man continued, “But for my father that wasn’t enough. My bar mitzvah was coming up and he wanted that at least on that day that I wear a complete set of tefillin. He had heard that in a barracks down the road, a man who had been killed had a complete pair of tefillin.

“On the morning of my bar mitzvah, my father, at great risk, went out early to the other barracks to get the tefillin. I was waiting by the window with trepidation. In the distance I could see him rushing to get back. As he came closer I could see that he was carrying something cupped in his hands.

“As he got to the barracks, a Nazi stepped out from behind a tree and shot and killed him right before my eyes! When the Nazi left I ran out and took the pouch of tefillin that lay on the ground next to my father. I managed to hide it.”

The old man peered angrily at Mordechai and said vehemently, “How can anyone pray to a G-d Who would kill a boy’s father right in front of him? I can’t!”

The man pointed to the dresser against the wall and said, “Open the top drawer.”

In the drawer Mordechai saw an old black tefillin pouch, crusted from many years of not being used. “Bring me the pouch,” the man ordered. Mordechai complied.

The man opened it and took out an old pair of tefillin. “This is what my father was carrying on that fateful day. I keep it to show people what my father died for, these dirty black boxes and straps. These were the last things I got from my father.”

Mordechai was stunned. He had no words — no comfort to give. He could only pity the poor man who had lived his life in anger, bitterness, and sadness. “I’m sorry,” he finally stammered softly. “I didn’t realize.” Mordechai left the room resolved never to come back to the man again. When he came home that evening, he couldn’t eat or sleep.

He returned to the home the next day, but avoided the old man’s room. A few days later, as Mordechai was helping the men who had come to the synagogue, one of the elderly wanted to recite the prayer said on the anniversary of a death, one that required a quorum.

“I have yahrzeit today and I need to say Kaddish,” the elderly man beseeched. “We only have nine men here today. You think you could get a tenth?”

Mordechai had already made his rounds that morning and had been refused by many of the residents. They were too tired, not interested or half asleep. The only one he hadn’t approached was the old man on the second floor.

Reluctantly and hesitantly he went upstairs. He knew the old man would scold him, but he still had to make an effort. He knocked on the door gently and announced himself.

“It’s you again?” the old man asked.

“I’m so sorry to trouble you,” Mordechai said softly, “but there’s a man in synagogue who needs to say Kaddish today. We need you for a minyan. Would you mind coming just this one time?”

The old man looked up at Mordechai and said, “If I come this time, then you’ll leave me alone?”

Mordechai wasn’t expecting that response. “Yes,” he said in a whisper, “I won’t bother you again.”

To this day, Mordechai doesn’t know why he then said what he did. It could have infuriated the old man, but for some reason Mordechai blurted out, “Would you like to bring your tefillin?”

Mordechai braced himself for a bitter retort — but instead the man said again, “If I bring them, will you leave me alone?” “Yes,” Mordechai said, “I will leave you alone.”

“All right,” the man replied, “then wheel me downstairs and make sure that I’m in the back of the synagogue, so I can get out first.”

Mordechai wheeled the old man to the synagogue and brought him to the back. “May I help you?”

Mordechai asked as he took the tefillin out of the pouch. The gentleman put out his left hand. Mordechai helped him put on his tefillin and left the synagogue to do other work.

After the services, Mordechai returned and the synagogue was empty — except for the old man. He was still wearing his tefillin and tears were running down his cheeks. “Shall I get a doctor or a nurse?” Mordechai asked.

The man didn’t answer. Instead he was staring down at the straps of tefillin wrapped on his left arm, caressing them with his right hand and repeating over and over, “Tatte, Tatte [Father, Father], it feels so right.”

The old man then looked up at Mordechai and said, “For the last half hour I’ve felt so connected to my Tatte. I feel as though he has come back to me.”

Mordechai took the man back to his room and as he was about to leave, the old man said, “Please come back for me tomorrow.”

And so every morning Mordechai would go to the second floor and the old man would be waiting for him at the elevator holding his tefillin. Mordechai would wheel him into the synagogue where he would sit in the back wearing his tefillin, holding a siddur (prayer book), absorbed in his thoughts.

One morning Mordechai got off the elevator on the second floor but the man wasn’t there. He hurried to his room, but his bed was empty. Instinctively he became afraid. He ran to the nurses’ station and asked where the gentleman was — and they told him.

He had been rushed to the hospital the previous afternoon and late in the day he had had a stroke and died.

A few days later, Mordechai was given an award by the Jewish home for his work as a volunteer. After the ceremonies a woman approached him and thanked him for all he had done for her. Mordechai had no recollection of the woman. “Excuse me,” Mordechai said, “do I know you?”

“I am the daughter of that man you helped,” she said softly. “He was my father and you did so much for him. You made his last days so comfortable. When he was in the hospital he called me frantically and asked me to bring him his tefillin. He wanted to pray one more time with them. I helped him with his tefillin in the hospital, and then he had his stroke.”

He died wearing them.

Bound to his Father — in Heaven.

Heard from Rabbi Zvi Teitelbaum, principal of the Yeshiva of Greater Washington in Silver Spring, Maryland, who I thank for sharing it with me.

Tell us what you think!

Thank you for your comment!

It will be published after approval by the Editor.